Yesterday it was a map, today it’s a chart.

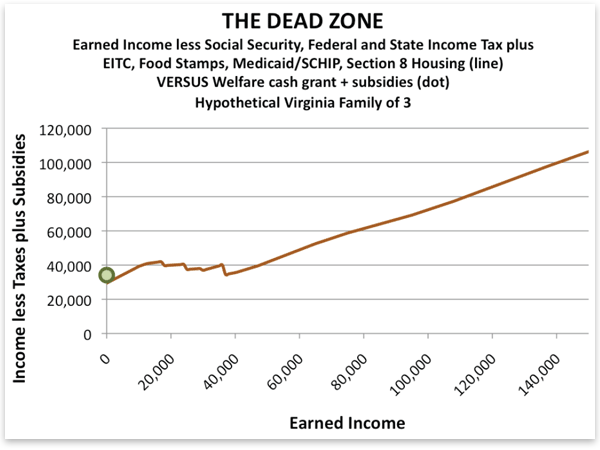

The point of this one is to say that, to be part of the world’s richest 1%, all you have to do is make $34,900 a year, after taxes.

That’s per person by household, of course, so if you’ve got a significant other, double it, and if you’ve got a couple of kids, quadruple it. It raises the bar a bit, but the big shocker is: 29 million, or almost half, of the world’s richest 1% are Americans, just like you!

Then there’s some other countries, take a look…

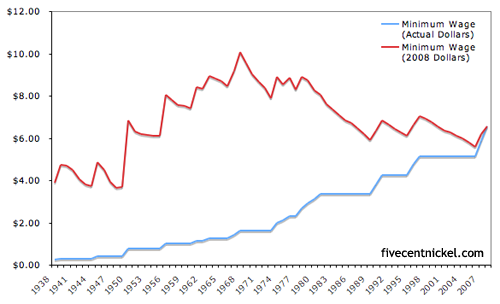

Now, this chart was part of an article on CNNMoney only a month ago, but we are told the data is from 2005. Then you count the little chart people, find only 60, and rightly exclaim, “Hey, we hit 6 billion in 1999.” For 2005, this chart would need four or five more people depending on which way you round it. It might not seem like much or that long of a time, but world GDP went from $40B to $60B in the same period. The question is, how would it change our $34,900 number?

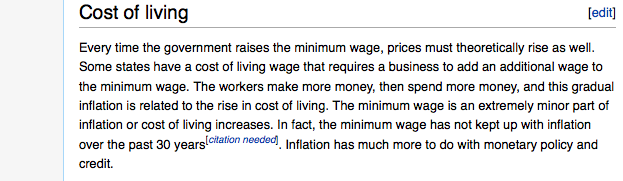

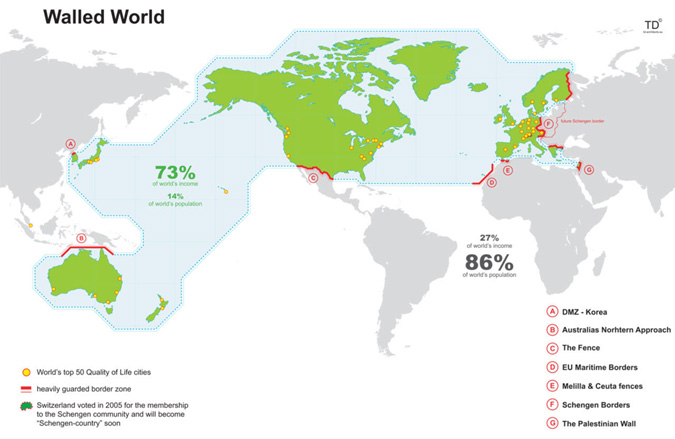

But say you do top that number, then look around your surroundings and rightly exclaim, “Hey, I’m not rich.” Just read the end of the article, silly. We’re talking about the entire world here. The world in which the global median income is $1,225/year. “In the grand scheme of things, even the poorest 5% of Americans are better off financially than two thirds of the entire world.” … That’s where the record skips. If you want to hear some reactions to this conclusion, check out the 1,000+ comments that have piled up. They range from pointing out the differences in cost of living around the world to accusing the writer of trying to take the heat off America’s 1%.

The disconnect is from measuring richness by income, as opposed to wealth. Yes, remember wealth. That’s what you’re missing. Assets. Your life should make sense again as soon as you hear that it takes $500,000 of assets to put you into the richest 1% worldwide.

How many little chart people would the U.S. get in this scenario? 37%, or 22 people. The chart above was only off by 11%, but it completely missed the boat on Japan, which should have 16 people. Anyway, what about the American 1%? How much yearly income does it take to get in that club? Well if you believe CNNMoney, they say it was $343, 927 in 2009, a measly 10 times what they were selling last month.

And before you think they might be trying to show both sides, note that this second article starts out by baiting you with the idea that it would take a million dollar income to be in the top 1%. Surprise, you only need a third of a million!  Or, 37 times what the poorest 20% of Americans make on average, 14 times the next, 7.7 times the middle, and 4 times the fourth quintile.

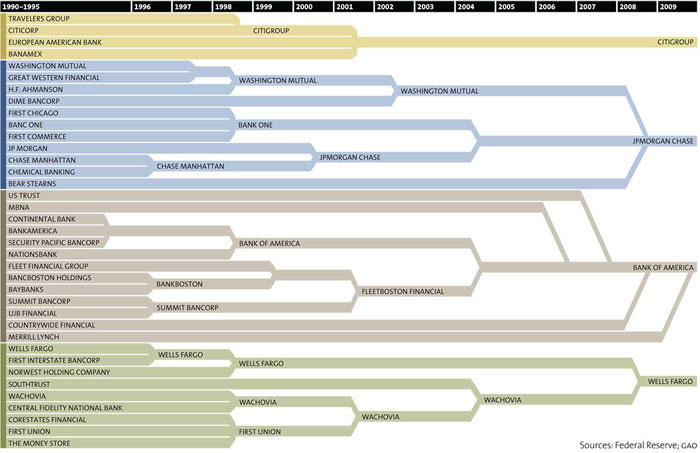

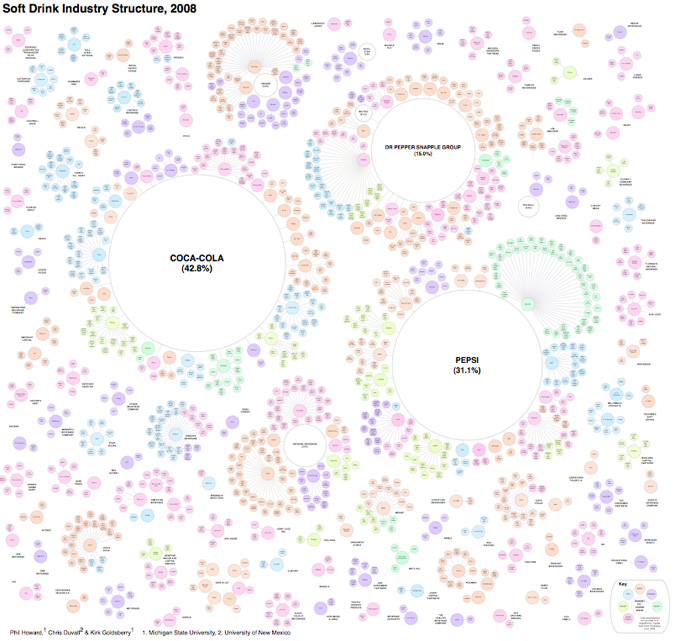

As ThinkProgress would love to explain further, the American 1% owns 40% of the nation’s wealth, including 50% of all U.S. stocks, bonds and mutual funds, and takes home 24% of the nation’s income.

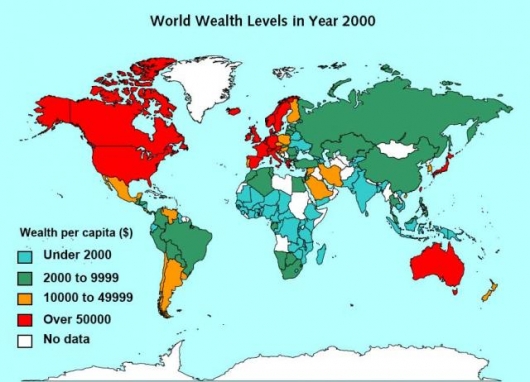

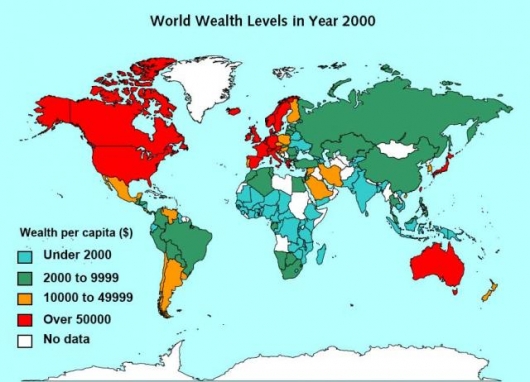

When it comes to world wealth, it looks a lot like yesterday’s map.

And back where we started, the crowd walks away wondering what it was all about anyhow.

[Map from

World Institute for Development Economics Research via

Gizmag]